CHAPTER 4: CINEMATOGRAPHY

Cinematography

The role of cinematography in storytelling is two-fold: first, the cinematography describes a space that is convincingly “realistic” and secondly the cinematography describes a particular point of view, a subjectivity, through which we are told about this world. Each story has specific variables that might change these two cinematography roles. For example, a fantasy story set in an imaginary place might not care about creating “realism”, per se. But the cinematography will be used to establish a convincing place that feels emotionally real, if not “real” by the standards of our world. Or, for example, a story might not be from any particular point of view – it might not have a narrator or a sympathetic main hero to follow. Just the same, the cinematography will still use immersive techniques to make us follow and invest in the camera as it portrays an omniscient view of the story.

Camera Placement

Though we might not always realize it, where the camera is placed with relation to the scene gives us a great amount of information. We generally like to look into our characters’ faces, at eye-level, so any deviation from this standard position reads as meaningful. A low-height camera might cut off faces entirely, focusing on knees or feet if characters are standing. Or in Yasujirō Ozu’s films like Tokyo Story (1953), for example, a low camera height is needed to showcase characters sitting on Japanese tatami mats. In this case, the camera is adjusted so that we can still stare into characters’ faces as they sit at ground-level. The camera brings us down to a domestic ground and, in turn, we feel as though we are sitting with the characters in an intimate, familial way.

A high-height camera films well above characters’ faces, perhaps staring out at the horizon like a bird, perched on a tree. Looking down from this vantage point onto a character, the camera would take on a high angle, distorting the character’s body. From a high angle, we would see the character’s head loom large and their body would look very small and very vulnerable, as in Avengers (Whedon, 2012). It is no surprise that high angle shots generally evoke a sense of power or knowledge over the characters who are in frame. This is the point of view of a mobster, looking down on his victim. And the high angle can also represent a more abstract metaphor of judgement, as in Alfred Hitchcock’s and Martin Scorsese’s films, which use high angle shots in moments of ethical dilemma.

Alternatively, a shot that represents a victim’s point of view, looking at a threatening man with a knife, as in Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009), would likely use a low angle. In this way, the camera makes the audience feel a sense of vulnerability and powerlessness by making us feel small while the character on screen looms large above us. Additionally, low angle cameras tend to distort characters’ faces, making them look unflattering – this further places us in the victim’s point of view by distancing us from a distorted, monstrous face. In moments of psychological turmoil or extreme power imbalance, the camera might tilt on its axis to create a canted angle, also called a Dutch angle. This technique has been used since silent cinema to evoke a sense of unease in the audience. In the 1950s, the Dutch angle was used excessively in Rebel Without a Cause (Ray, 1955) to show power shifts between teenagers and figures of authority (parents, police officers). In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), Gilliam cants his camera when characters become drug-induced – the camera visually represents the feeling of being off-kilter.

Low-height camera: Camera is placed low to the ground, without a tilt. This shot may capture someone on ground-level, or it could capture feet.

High-height camera: Camera is placed high above the ground to capture something in the air or a distant view.

High-angle shot: Camera is tilted down to film an object or character from above. This shot often makes a character look vulnerable and small.

Low-angle shot: Camera is tilted up to film an object or character from below. This shot often makes a character look powerful and large.

Canted-angle / Dutch-angle shot: Camera is tilted on its axis to evoke imbalance, anxiety, or a mental break.

Camera Movement

Though movement in the frame is most obviously carried by the actors who move across the set, the camera contributes greatly to the sense of dynamism in a shot. In fact, a shot might feature static characters and still be considered dynamic through the motion that the camera contributes to the scene.

Two very simple movements can be achieved with a static camera on a tripod or on a standing cameraman: a tilt and a pan. By swiveling the camera from side to side, a pan represents the turn of a human head. This appears to be a very natural movement to the viewer. Just as we turn our heads side to side in order to read a room, the camera’s pan creates an eyeline view and reads the fictional space like a book. It is no wonder that in Western cinema, panning from left to right feels the most natural, just like reading a Western book, from left to right. A tilt brings the camera-head up or down and represents a vertical scan. This feels less natural than a pan, since we generally spend less time looking up and looking down when we read our environments. But the tilt becomes a very important tool for specific cinema moments, like reading characters from head to toe or finding hidden figures in unusual spaces, like ceilings, in horror films.

A third, less used, camera tactic is a pedestal, where the camera remains level but is lifted up on its tripod to read an environment up and down without tilting. In Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), the mansion Xanadu is revealed to us with a pedestal. We first see a “No Trespassing” sign, then the camera pedestals up over gates until we finally have an answer to the question of what should not be trespassed: the mansion Xanadu sitting on a hill in the distance with the gate’s large “K” (for Kane) looming large in the foreground.

In order to get even more motion in a shot, we might place the camera stand onto a moving object. In early cinema history, we see cameras placed on trains, boats, planes, and cars to get the shot to move quickly in a stable way. Since the camera, for most of cinema history, has been extremely heavy, it has been hard to create a steady image using just a cameraman’s body (a hand-held shot). It is not until cameras became more lightweight in the 1960s that extensive use of the hand-held shot became an option for cinema, and even then it was considered an experimental strategy used for European art films or for documentary footage.

Generally, a stable moving shot is created using a dolly. A track is laid out for the shot that choreographs the camera’s path with the actor’s, and a platform is set up on this track to move the camera and the cinematographer together as the scene is filmed. These dollies can be set up in a straight line or in a curve, on a paved street or in a wild landscape. The main restriction of a dolly shot is that its movement must conform to the ground.

The effect of a tracking shot is a smooth movement, often using a dolly, that tracks a character as they walk through their environment. When we watch a tracking shot, we are unaware of the dolly setup – it becomes invisible to the viewer because it is an unobtrusive movement. Its smoothness allows us to feel as though we are with the character, walking side-by-side with them and investing in their problems, their concerns, and their emotions. The dolly shot brings us closer to characters and its invisibility helps to enforce our identification with them.

Another type of dolly shot places the actor on a dolly too. The double dolly shot is associated most closely with filmmaker Spike Lee, who uses the technique in nearly every one of his films. The effect of the double dolly shot is an interior experience, an extreme closeness with the mental state of a character. When the camera’s dolly and the actor’s dolly are synchronized so that they are moving the exact same pace, a different one than the rest of the environment, we feel as though we have been let in to such a personal experience that no one else can understand but us. This effect brings us even closer to the character and helps us to identify even more deeply with them through a technique that feels dreamy and isolated.

A more complicated and freer setup for a camera movement is a crane shot, in which the camera and cinematographer sit on a crane platform that can take them up into the air to shoot a scene from above. This is, of course, a more complicated setup because the camera movement must be coordinated with much heavier equipment and requires more safety measures. The effect of a crane shot is an omniscient, powerful gaze that can see the story world from above, from a viewpoint that the characters do not have access to. Films might use a crane for an establishing shot to orient the viewer in space before cutting in to the scene itself. Or films might use the crane shot to create a long take that scans the set from many angles. Hollywood musicals of the 1930s by Busby Berkeley, like 42nd Street (1933), utilized the crane shot to create detailed geometries with dancers’ bodies, filmed from above. The effect is kaleidoscopic as human bodies are turned into abstract shapes from high, flying angles that feel thrillingly inhuman.

Perhaps the most famous long-take crane shot was created by Orson Welles for the opening of his Touch of Evil (1958). In this scene, the camera sneaks along a wall and witnesses a bomb being placed into the trunk of a car. Then the camera lifts into the air as the car drives away into city streets. For over three minutes, the camera loses and catches up to the car, sometimes dipping down to street level, sometimes lifting up to see the street from the sky. Welles teases his audience: he lets the tense scenario be examined from many angles and he lets the car be lost and found again. When the car finally explodes, it does so with a sharp cut that feels like an explosion of editing, since the three-minute long take has made us so accustomed to the smooth, omniscient crane setting.

See Chapter 6 for more on Touch of Evil.

The latest technological innovation for a flying camera effect is the drone shot, which can now replace a helicopter- or plane-mounted camera shot. A drone shot, in which a drone-mounted camera films from the air, can be used for establishing shots, and the footage is often rendered in slow motion for a smoother effect. It is difficult, however, to use a drone-mounted camera to film close-ups and actor details. Crane shots are still the industry standard for omniscient long takes that include both establishing shots and medium shots or close-ups in the same footage.

The crane shot and drone shot are both freer forms of filming than the dolly in that they are able to move in all directions, unbounded by a track that must be laid out in advance of shooting. The dolly shot is restricted to the types of terrain that are track-friendly, and its camera is also unable to look at the ground for fear of filming its own track setup. A piece of technology developed in 1975, the Steadicam fixed many dolly track problems. Because the Steadicam is attached to the cameraman’s body with various stabilizers, it creates a smooth movement even when the cameraman jostles it with rough footsteps or uneven terrain. Like a dolly track, the Steadicam shot is smooth and immersive. But unlike a dolly track, the Steadicam shot can move into spaces unfriendly to a track and can shoot the ground, where a track would normally have been laid. Though the Steadicam technology was used sparsely in several late-1970s films, the most extensive use of the Steadicam is credited to The Shining (Kubrick, 1980), in which characters are tracked low to the ground as they move through many hallway corners in single takes. Such complicated shots would be difficult to capture in a dolly shot. The Steadicam gaze, floating along so close to the ground, registers to the viewer as a creeping, ghostly presence, a look that fits this horror film’s themes perfectly.

Several 1990s films have paid homage to Touch of Evil’s famous crane opening by contemporizing it with a Steadicam. Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) uses a Steadicam to replicate the omniscient stalking that Touch of Evil had become so famous for. The camera follows two characters in a three-minute long take as they move from their parked car into the backdoor of the club Copacabana and through the kitchen into the club. The Steadicam gives a floaty effect, so that the viewer feels like an insect following the characters through tight, crowded spaces. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997) combines both techniques: the crane shot and the Steadicam. The film opens with a three-minute long take that starts as a crane shot that tilts and flies down to the ground, then seamlessly transitions to a Steadicam that follows characters into a club. The camera moves us from the sky to the street to the interior, making us feel both like an omniscient observer and a participant in the scene.

Of course, if a filmmaker desires a cheap or a rough look to camera movement, then a handheld shaky cam shot can be preferable to the more expensive and complicated options of a dolly, crane, or Steadicam. Handheld cameras have long been used for documentary film because they provide freedom of movement and can more easily capture unplanned events. Many of these documentary handheld cameras inadvertently create a shaky camera look, and this look has become an aesthetic in narrative cinema that seeks a less sleek style. For example, mockumentaries replicate the shaky cam aesthetic in order to feel more authentic, more like a true documentary that aims to capture un-staged events. More recently, found footage horror films like The Blair Witch Project (Sánchez/Myrick, 1999) and Paranormal Activity (Peli, 2007) have adopted shaky cam shots in order to feel more realistic, and thus more horrific. Some light touches of shaky cam shots can be found now in most blockbuster films to evoke authenticity. Car chase sequences in recent action films, like Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015) and Quantum of Solace (Forster, 2008), use small, almost imperceptible inserts of shaky cam footage, taken from a camera attached to the side of a vehicle, in order to give authentic texture to the chase. These shots tend to be made with lesser quality cameras than the film generally, and so the texture of the footage feels closer to a documentary than a Blockbuster film. Though the audience is not meant to explicitly notice these small shots edited into the sequence, they do impart a feeling of reliability to what is otherwise a rather unbelievable action scenario.

Pan: Camera swivels from side to side.

Tilt: Camera tilts up or down on its axis.

Pedestal: Camera axis is lifted up or down while camera itself remains level.

Dolly shot: Camera is placed on a moving platform attached to a track. The track can be set up in a line or a curve. The cinematographer sits on the platform (dolly) with the camera as it is pushed along the track.

Double dolly shot: Both camera and actor sit on dollies whose movement is linked. Creates a dream-like effect of interiority.

Tracking shot: A smooth camera movement that follows (tracks) a character as they move. Often achieved with a dolly or Steadicam.

Crane shot: Camera and cinematographer sit on a crane, which films from above and can “fly” over the set.

Steadicam: Technology developed by Garrett Brown in the 1970s where the camera can be attached to the cinematographer’s body with stabilizer mounts to create a smooth movement while walking.

Shaky cam shot: A rough, bumpy shot often associated with Direct Cinema documentaries of the 1960. Can be achieved with a handheld camera on set or with computer graphics in post-production.

Lenses

Camera distance from a character and camera movement alongside a character influences the feeling we have towards them. For example, close-ups of actors and objects imbue them with great importance in the narrative and extreme long shots orient the audience in a time and place. A filmmaker’s choice in camera distance can also determine their choice of camera lens because different camera lenses capture different amounts of set space. Put simply, a wide- -angle lens captures less range than a telephoto lens does. Why this is true is a bit more complicated, but worth delving into to better understand filmmaking choices and their meanings.

Lenses are available on a scale of sizes based on their focal length. On the small end, a wide-angle lens can range from 24mm to 35mm. It will capture a wide amount of space at a close range. On the long end, a telephoto lens can range from 70mm to 300mm or more. It will capture a narrow amount of space at a long range. (See Diagram 1)

Each of these types of lenses will capture the image with particular qualities. One advantage to the wide-angle lens is that you can film from very close to the object. For example, when filming The Life Aquatic (2004), Wes Anderson wanted to capture the entirety of a ship set that was built on a sound stage in the frame of his camera. To do this, he had to order a very wide-angle lens (25mm), even wider than his usual 40mm, since the sound stage dimensions kept his camera so close to the set. But the disadvantage of the wide-angle lens is that “bulging” can occur along the edges of the frame. The lens is so rounded that parallel lines on set will start to bend in towards each other at the edges. This rounded “bulging” effect is most pronounced at the smallest focal lengths (8mm to 14mm), often called “fish-eye” lenses for this reason.

What is actually happening within the wide-angle lens is that the shorter focal length creates a wider angle of vision that is captured by the lens, thus the name “wide-angle”. (See Diagram 2) As a result of this wide angle and the shape of the lens, the objects in frame have a more distanced relationship to each other. Planes in space look as though they are set far apart from each other, creating the look of deep space that is cavernous and vast. Using a wide-angle lens can make characters feel emotionally distanced from one another, or it can make a character look as though they are belittled by their environment. In Wes Anderson’s films, like Hotel Chevalier (2007), the aesthetic of a wide-angle lens supports his common film themes of distanced relationships and lack of true human connection.

One classic application of the wide-angle lens in the late 1930s and 1940s was the technique of , developed in French Poetic Realism and popularized by Orson Welles in Hollywood cinema. Deep focus involves several carefully planned elements to achieve the effect of an all-perceiving and meaningful camera eye. To achieve deep focus, a filmmaker must use a wide-angle lens to achieve deep space through a short focal length. They must close the lens aperture to create a larger depth of field, the range of distance that creates sharp focus. And they must fill the set with light so that the camera can capture set detail even with a small aperture. Once all of these elements of deep focus are in place, the mise-en-scène will be captured in crisp, sharp focus in every plane, from the foreground to the background of the set. The effect is simultaneous vision of foreground and background without the need for cutting, camera movement, or focus pulling.

Jean Renoir and Orson Welles used the deep focus technique for metaphoric purposes: since the wide-angle lens creates the illusion of distance between planes, a character moving away from the camera will quickly appear smaller and smaller within the frame. In Welles’ Citizen Kane, the character Kane moves away from the camera towards the back of a room while accountants count his money in the foreground of the frame. As the accountants dribble his money away, Kane appears smaller and smaller until he is just an insignificant figure leaning against the back wall. As we hear about his money disappearing, so we see Kane’s body disappear too. This visual metaphor, allowed by the distancing effect of the wide-angle lens paired with deep focus, allows us to see how closely Kane is tied to his economics.

Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

For the opposite effect, a telephoto lens can be used to create an extreme closeness among characters or crowdedness within the environment. A telephoto lens is quite long, so the objects that it captures must be set very far away from camera. As a result of this physical distance between camera and objects, the objects appear to be relatively close to one another. In the telephoto lens, planes in space look as though they have been compressed together and they are sitting right next to each other. This makes characters feel as though they are in very close proximity, and it makes the environment look quite full and dense. Telephoto lenses are used often in cityscapes to make streets look fuller and more crowded, like in Tootsie (Pollack, 1982), where Michael is framed to look like he blends in while costumed as “Dorothy”.

The disadvantage to the telephoto lens is that it has a very shallow depth of field, which makes it hard to keep a moving object in focus. In a crowd filmed with a telephoto lens, a hero might be in focus but the person right behind her and right in front of her are out of focus. Therefore, as she moves towards the camera, the cameraman must move the camera with her at her pace in order to keep her in focus. If done correctly, the people around her will look like a hazy sea of bodies and she will emerge as a crisp heroic image among them.

Of course, one way for a filmmaker to not be forced make the choice between a wide-angle lens and a telephoto lens is to use a zoom lens, otherwise known as a variable lens. A zoom lens can shift the focal length of its lens to make it short or long. Unlike a fixed lens, like a wide-angle or telephoto, the zoom lens moves fluidly between several settings to allow for the same lens to have many lens options. The disadvantage of the zoom lens, however, is that it is heavier, thus less portable, and has smaller apertures, so it is slower and needs more light than a fixed lens to create the best image.

The zoom lens became so common and overused by the 1970s and 1980s that it gained the reputation of being a “lazy” filmmaking technique. But the 1950s gave us a rather unique effect that could only have been achieved using the technology of a zoom lens: the dolly zoom. This effect was developed by Hitchcock for his film Vertigo (1958). After fainting at a party, Hitchcock wanted to cinematically recreate the feeling of dizziness, which he could only describe as “vertigo”. After many experiments, his special effects team landed on a visual trick that combined a dolly track and a zoom lens. The dolly zoom, also called the Vertigo effect, pulls a camera away from an object as the camera lens zooms in on the object. The zoom changes the lens by which the object is captured – first it is a wide-angle lens, then it becomes a telephoto lens. The dolly track out keeps the object occupying the same space of the frame as the zoom becomes a telephoto lens. By keeping the object generally in the same space on the screen but meanwhile changing the focal length, the environment around the object will appear to move while the object appears to stay static.

In a dolly zoom that dollies away while zooming in, the environment will at first feel vast and elongated, but as the lens zooms in, the environment will become compressed and dense. The effect is environmental distortion that seems to be a representation of what the character is feeling internally. Dolly zooms are often used in times of critical peril: a psychological crisis, a sudden realization, or a feeling of powerlessness. They are used most famously in Vertigo and Jaws (Spielberg, 1975), but have become quite common in every genre and in every cinematic medium, including TV and commercials. What was once a unique solution using technological innovation has become a widely accepted and standardized metaphor.

Wide-angle lens: Range in focal length from 24mm to 35mm. Captures a wide amount of space at close range, which makes it optimal for filming big sets. The shape of the wide-angle lens creates “bulging” at the edges of the frame and creates distance between objects.

Telephoto lens: Range in focal length from 70mm to 300mm or more. Captures a long range of space, which makes it optimal for filming at long distances. The distance of the telephoto lens flattens planes of space in the frame, making objects appear extremely close together.

Deep focus: A style developed in the late 1930s, often attributed to Orson Welles. Creates sharp focus through several planes of space in the frame. Requires a wide-angle lens, small aperture, set light, and deep space in the mise-en-scène.

Depth of field: The range of distance that is kept in sharp focus within the frame. A shallow depth of field keeps a small amount of space in focus. A large depth of field keeps a large amount of space in focus.

Zoom lens: A variable lens that can move between several focal lengths, potentially creating both wide-angle and telephoto effects.

Dolly zoom / Vertigo effect: A style developed by Hitchcock for his film Vertigo (1958) where the environment appears to contract or expand. Achieved with a dolly track and zoom lens.

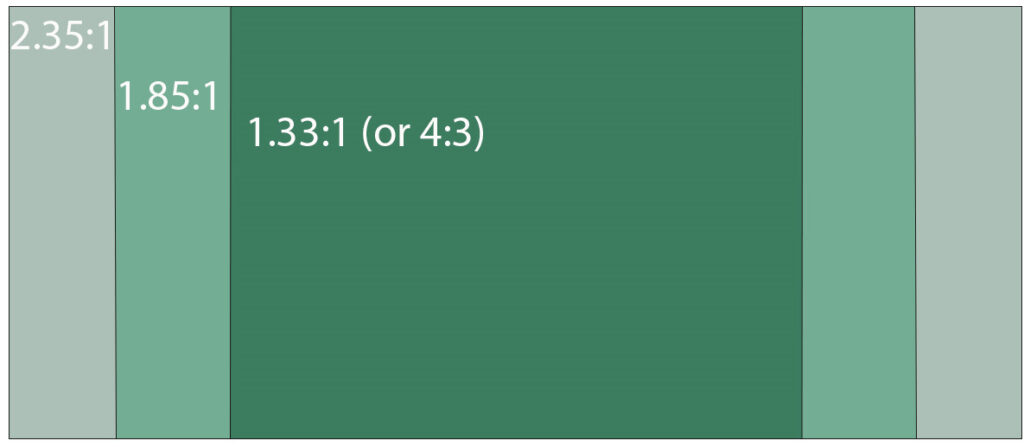

Aspect Ratio

There has always been a relationship between the shape of film stock and the shape of theater projection. The conventions for aspect ratio, or the ratio of width to height of a screen, has changed over cinema history as new lenses have been developed and standards for projection quality has increased. Silent cinema started with a 1.33:1 aspect ratio for 35mm films and TV matched this aspect ratio so that movies originally filmed in 35mm could be easily translated to TV screens. This squarish format worked well for close-ups, since a character’s face fills the shape in a comfortable way.

When theater attendance dropped in the 1950s due to the popularization of TV, the cinema industry upgraded its technology to allow for newer widescreen standards. The wider aspect ratios – first 1.85:1, then 2:35.1 – created a more dynamic image viewing experience than TV could allow and brought many viewers back into theaters. But filmmakers found the new shape challenging to film in because many of their previously used framings looked awkward with a wider screen. Close-ups no longer filled the shape. Two-shots also didn’t fill enough of the space. So filmmakers started to place more and more characters into the frame to fill it. Often, so many characters were standing side-by-side to fill the frame that they looked like they were pinned to a line – this look was called clothesline staging and was commonly criticized by filmmakers. A film like Rebel Without a Cause (Ray, 1955), which used a new anamorphic widescreen lens called CinemaScope, found creative ways to fill the frame without setting up simplistic clothesline staging. Rebel’s set is carefully organized in levels, using architectural features, cars, or furniture, to allow characters to be positioned throughout the frame horizontally and vertically, not just in a line. The set also carves out aperture framings in the background, like windows and doorways, to allow for multiple mini-frames, cutting up the wide space, in which characters can appear. And the camera is often placed at a low angle or a canted angle so that more of the rectangular frame is filled by characters’ bodies.

First introduced to the public in the late 1940s, the anamorphic lens was one of the many innovations that the film industry tried out in order to compete with TV technologies, first introduced to the public in the late 1940s. To lure audiences back into theaters for unique experiences, studios tried 3D films, gimmicks, and giant screens similar to our current Imax theaters. 3D film technology was borrowed from comic books, using the same principle of anaglyph (red and blue) glasses. A polarization option was also developed in which two projectors would synchronize two separate images. Cinema gimmicks would be marketed as theatrical experiences most often in B-film horror. William Castle, the self-proclaimed “king of gimmicks”, would scare his audiences with skeletons flying across the theater, buzzers attached to seats, and life insurance taken out in audience members’ names. Such gimmicks promised a unique theater experience that could not be replicated at home. Widescreen formats like Cinerama promised an epic film experience in which three projectors created an image three times as large as a regular screen across a curved wall. Though very impressive, Cinerama had so many technical issues, like easily unsynched projectors, that it did not catch on like CinemaScope’s anamorphic lens, which captured image with one camera and projected it in nearly as wide of a format with only one projector.

To lure audiences back into theaters for unique experiences, studios tried 3D films, gimmicks, and giant screens similar to Imax theaters.

Contemporary widescreen cinema has now been standardized to a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, but some filmmakers will play with the size of the image in order to evoke a previous cinema era. Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) is a great example of this principle, as it organizes the time period of each scene according to its appropriate cinema aspect ratio. The most contemporary scenes, set in 1985, are presented in 1.85:1; the scenes set in 1968 are in 2:35:1, an anamorphic aspect ratio; the scenes set in 1932 are in 1.37:1, the standard Academy ratio of the 1930s. Many viewers overlook the changing shapes of their screens while watching this film. The different aspect ratios, though, are meant to pay homage to differing film styles and the screen frame restrictions must be used uniquely and creatively for each era, as filmmakers of past aspect ratio transitions have had to do.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (Anderson, 2014)

Aspect ratio: The ratio of width to height of a screen.

Widescreen: Aspect ratio developed in the 1950s to create a bigger, more exciting image for theaters.

Anamorphic widescreen lens: A specific lens developed to capture more image onto the film stock through compression, which then would be expanded in projection. Had similar distortion problem as other wide- -angle lenses.

Gimmick: An extraneous device or event meant to attract attention. Examples are marketing campaignsand 4D theater tricks.

“We all have a common interest: bigger and more horrible monsters —

and I’m just the monster to bring them to you.”

-William Castle, ‘King of the Gimmick’

Early Film Gimmicks

Hollywood has always needed an audience to do what it does best: sell movies. By 1910, theater owners regularly developed their own promotional materials for films. They did this because it was often cost-prohibitive to advertise in local newspapers. Instead, they borrowed methods from the circus tradition of P.T Barnum, making their own posters, pressbooks, and even hiring barkers to create buzz. Film studios quickly took notice of a growing need to shape public opinion about their movies playing at other people’s theaters. In 1915, Paramount was among the first studios to develop their own “Exploitation Department”, which provided theater owners with gimmicks, stunts, and “tie up” advertising that included buy-in from local businesses. People couldn’t avoid seeing or hearing about a film when it came to town, if it was properly exploited. This would create quick amusement, word of mouth, and ultimately, paying customers.

For instance, in 1918, Harry Reichenbach, a prolific publicist and provocateur, pulled off a stunt to promote the upcoming Tarzan of the Apes. As the story goes, Reichenbach inquired with the Belleclaire Hotel in New York if they could accommodate a concert pianist with a particular penchant for eating huge quantities of meat. The hotel agreed and provided the supposed pianist, Mr. T.R. Zann, with a steady supply of meat. After the hotel got wind that there was no music being played, as well as a whiff of some decaying meat, they inquired about Mr. Zann. Management, followed by journalists that were likely told about the story, forcibly opened Zann’s hotel room door to find a full-sized lion had taken up residence there. The publicity from the stunt gave the film a huge opening and made it successful.

Reichenbach and other Exploitation Managers actively worked to put their rhetoric in the mouths of both journalists and would-be filmgoers. Often, word of mouth would spin itself into thick lore, with supporters and detractors alike promoting a film after getting taken in by an enticing gimmick. By the 1920s, news outlets were getting wise to the schemes employed by these movie exploiters. A 1924 headline in Motion Picture Magazine read “The Movies Outdo Barnum: And Poor Pictures Make Money Because of Clever and Extensive Exploitation While Good Pictures May Fail Thru Lack of It”.

Throughout the 1930s and 40s, drugs and sex became popular exploitative topics in films. Reefer Madness (1936) was a repackaged morality tale originally made by a church group, with scintillating scenes added to exploit drug use and sex alluded to in the film. Mom and Dad (1945), relied on similar techniques. Kroger Babb produced a “sex hygeine” film that, on the surface, sought to educate audiences about the dangers of sex. The film featured live births, seen for the first time in theaters. Babb exploited this by bombarding small towns with tie-up advertising, had paid presenters write fabricated letters to newspapers protesting the film, and required male/female segregated screenings, to heighten controversy surrounding it. Keeping moral and educational lessons intact allowed producers to skate past the newly implemented Hays Code of film censorship, while still exploiting audiences’ want for illicit scenes.

Though studios had entire departments dedicated to exploiting a film’s basic features, no single producer or director had more gimmicks up their sleeve than William Castle. His first memorable gimmick came as a stage director in the late 1930s, when he hired German actress Ellen Schwanneke. At the time, German actors were only permitted to act in plays first performed in Germany, during Nazi rule. Castle quickly wrote a script and had it translated into German. Schwanneke received an invitation from the Nazi party to perform the play in Germany, which Castle saw as a promotional opportunity. Castle claims that he wrote a telegram to the Nazi party, declining the invitation. In the press, he fanned sensationalism by referring to Schwanneke as “The Girl Who Said No to Hitler”. This got people talking and Castle kept the controversy going by defacing the theater himself with painted swastikas on the exterior. The play was well-attended as a result.

Castle would parlay his success in theater to a full career in film, making a name for himself through the 1940s and 50s as a B-movie director who delivered films on time and on budget. He flirted with 3-D in 1953 with the western Fort Ti, upon seeing the massive crowds for Bwana Devil (1952), noted for igniting the first wave of 3-D features in the United States. Castle practiced his aim and threw everything he could at the camera. He remarked to his wife upon seeing moviegoers ducking projectiles in the theater, “I’m not a director, I’m a great pitcher”.

During Castle’s heyday as a director, he utilized numerous technological “processes” that involved branding a live theater experience with catchy names. This was common at the time, as the film industry tried to promote the movie theater as offering more than television. For House on Haunted Hill (1959), Castle invented “Emergo”, where a skeleton would pop out of a box above the screen and sail across the theater, where young patrons would throw popcorn at it. For his seminal film, The Tingler (1959), Castle utilized “Percepto”, where he rigged plane wing deicer motors to the bottoms of theater seats. He coordinated with theater employees to buzz people’s butts when the film purported that The Tingler was loose in the theater.

Castle’s schemes became more complex over time, adding hired actors to pose as nurses in theater lobbies, planted audience members to “faint” at certain moments, and even “Coward’s Corner”, a branded box that patrons could retreat to if the film scared them too much. Theater owners often complained about putting on a Castle film in terms of cumbersome technology and gimmicks like the “Fright Break” for Homicidal (1961), which promised patrons their money back if they were too scared to continue. His legacy lives on today as the film industry is always looking to exploit the next great gimmick to entice audiences.

“EARLY FILM GIMMICKS” CONTRIBUTED BY

ALEX LUKENS

GEORGIA FILMMAKER &

LECTURER OF EMERGING MEDIA DESIGN

BALL STATE UNIVERSITY

Color

Experiments in film color can be traced back to the late 19th century, when some black & white film prints would be hand-colored with paints to create a “color” film projection. Color film cinematography has been patented with various techniques since the early 1900s. But the most widely used early color process in Hollywood was Technicolor, used for major studio pictures like The Wizard of Oz (1939), Gone with the Wind (1939), and Fantasia (1940). Each subsequent color film technology fixed some technical issues, like light, camera, and projection requirements.

Since the popularization of color film stock, cinematography has been interested in the psychological and emotional effect that color and color combinations have on the viewer. We have already seen that color has symbolic value in film (Chapter 2: Mise-en-scène). Audience associations with color are culturally defined, so the same color in two separate cultures might have opposing meanings. For example, the color red has associations of power and warning in Western cultures, but in many Eastern cultures, red is associated with weddings and beauty. So color symbolism does not always translate perfectly across the world. But film also creates its own color association language by color-coding films according to their genres. For example, psychological thrillers tend to be cast green, horror films tend to have a blue cast, and fantasy films tend to be cast purple.

See Chapter 2 for more on color.

These overall color casts are only somewhat created on set through the art departments. Most of the color hues are created with the post-production process of color grading, which creates consistent color quality across all shots and all scenes. This color technique can enhance and change the costumes, the set, the light, and even skin tone. Color correction helps footage from multiple shoots over many days and locations look like they belong in the same time and space. In many ways, it covers over any continuity errors by fixing unnatural contrast, lighting, and color levels. Color grading allows for films to take on new color hues to provide an overall sense of world immersion. Many of these color grading choices work alongside lighting to create mood in the scene and in the film. We can see the progression of these choices within a franchise like Harry Potter, whose first film has a magical golden glow and whose third film turns an icy blue with dark shadows. In this way, Harry Potter’s themes evolve alongside its color grading: as Harry Potter ages and matures, his world becomes less golden and more terrifying.

Not every film has a single generic color theme across all scenes. In fact, most genres use color palettes that combine multiple color hues and saturations to convey more complicated mood and tone through visual means. Three common color palettes – monochromatic, analogous, and complementary – use just a few colors to organically evoke composure or tension within the scene. A monochromatic color palette uses multiple saturations or values of the same color hue. For example, the film The Matrix (Wachowskis, 1999) uses different values of green across most matrix scenes. This gives the impression of a consistent world that runs by a single set of rules. An analogous color palette uses two or three neighboring colors to create a cohesiveness to the story world. For example, Her (Jonze, 2013) uses pinks, reds, and browns throughout most of the mise-en-scène to create a slightly futuristic but believable world. This color palette sounds a bit dull, but Jonze creates contrast in the environment by playing with saturation, using highly saturated pinks and very dampened browns. The effect is simultaneously naturalistic and enchanted. A complementary color palette uses two or more opposing colors to create tension in the story world. For example, Amélie (Jeunet, 2001) uses opposing reds and greens in nearly every scene to represent Amelie’s inner tension between her independence and her need for companionship. Lately, blockbusters have been critiqued for overusing the complementary colors teal and orange to aesthetically create tension in otherwise unmotivated scenes. We can clearly see this teal-orange tendency in recent blockbuster posters, which evoke a tone of dramatic conflict in a single image: Transformers (Bay, 2007), Blade Runner 2049 (Villeneuve, 2019), Brave (Chapman/Andrews, 2012), Dark Phoenix (Kinberg, 2019).

A less common color combination is a triadic color palette, which includes three complementary colors, arranged in a triangle on the color wheel. This type of palette is jarringly unnatural and is often used for discontinuity effect. Jacques Demy, part of the Left Bank Group in the French New Wave, famously used triadic color palettes in his musicals. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) boldly uses yellow, red, and blue in the same frame to create an artificiality to the musical when other elements, like singing and character motivation, remain quite naturalistic. Recently, La La Land (Chazelle, 2016) referenced this Demy yellow-red-blue color palette in many scenes where costumes and props clash to create a bold theatricality. Other scenes in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg create a triad of blue-pink-green and a tetrad of pink-green-blue-orange. Though these colors are dull in saturation to make them slightly more believable in the scene, the off-putting color combinations create the effect of unresolved tension in the characters’ interactions.

Digital color grading has created a greater efficiency in the area of film color. With the touch of a button, visual effects specialists can experiment with color casts, saturations, tone, and palettes. It is no wonder that in the past several decades, since access to this new technology, we have seen more vibrant colors on screen than can be captured with color film stock or with digital cameras. Many of our films have entered the realm of color fantasy, even when outside of the fantasy genre. But, perhaps ironically, our dramas and thrillers have become even more dark and muted as we enter an era of digital filmmaking and post-production that allows for shadows to take on more detail and nuance. So we see contemporary cinema pulled in two color directions: the excess of color and the desaturation of color. In fact, digital filmmaking has also seen a resurgence of black & white cinema, which is often filmed in color and then digitally transferred into black & white. Recent films like Ida (Pawlikowski, 2013), A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (Amirpour, 2014), and Roma (Cuarón, 2018) have won critical acclaim for their rich hues and contrast in black & white photography. Other contemporary black & white films, like The Lighthouse (Eggers, 2019), have received acclaim for their use of traditional lenses and black & white film stock to achieve a more textural and visceral viewing experience than digital cameras and techniques allow.

Color correction: Adjusts color hue, light, and saturation across shots to create cohesive sequences.

Color grading: Creates world immersion by casting scenes in a particular color hue.

Color palette: Combination of color hues and saturations to convey mood and tone through visual means. Includes monochromatic, analogous, complementary, and triadic palettes.

Black & white cinema: Films absent of color hues. Can be achieved with black & white film stock or in digital post-production.

Special Effects

The question of believability in cinema lies not only in the way that action in front of the camera is captured, but also in how the eye can be tricked into believing movie “magic”. Special effects have always been a part of film production, and many of the first special effects were created or inspired by theater magicians. Special effects in part work because they look believable, but some less authentic-looking effects work simply because the film has created such an immersive story world that the viewer is put into a suspension of disbelief.

Some classic special effects no longer look convincing to the contemporary viewer, but they are the basis for our more convincing visual effects of the digital age. Matte paintings, for example, which use paintings and, as we move into the digital age, 3D renderings of landscapes, are the predecessors of green screens. Rear projection, in which footage is projected onto a backdrop while the actor before it is filmed from the front, is the predecessor of travelling mattes and digital rotoscoping. The rear projection technique was used often for car shots to showcase characters conversing in the front seat while the environment flashes past them, and for high action sequences filmed in studio, like chases on foot, by boat, or even on horse-back.

Another common effect that has changed little since early cinema is slow motion and fast motion. With traditional film stock, the change in motion is achieved by adjusting the speed of image capture. With hand-crank cameras, the cameraman would overcrank the film stock in production so that when projected at a regular speed, the image would seem to move slowly. Similarly, for fast motion, the cameraman would undercrank the film stock so that the projection would appear to move quickly. Silent cinema often looks undercranked to us now because our projection standards have changed. In silent cinema, film stock was captured and projected at 16 frames per second (fps) but since the advent of sound cinema, the standards have adjusted to 24 fps. So, when projecting a 16 fps film at 24 fps, the film will appear to be in slightly fast motion.

See Chapter 1 and Chapter 8 for special effects and visual effects.

Slow motion has often been used to evoke despair, isolation, or inner turmoil. French Impressionist cinema of the 1920s famously used slow motion to explore characters’ inner emotions and psychology (See Ch 1: Film History). More contemporary films, like Casino (Scorsese, 1995) and Chungking Express (Wong, 1994), continue to use slow motion to express inner feelings: an isolating emotion, a hazy memory, a thought process, or the effect of alcohol or drugs. Slow motion can also give a “cool” factor to a character by extending their movement or to an action otherwise unseen by the human eye. Films like Reservoir Dogs (Tarantino, 1992) and The Usual Suspects (Singer, 1995) use this effect to show power in characters’ gait. Films like The Hurt Locker (Bigelow, 2008) and Drive (Refn, 2011) use this effect to expand time in order to appreciate the small moments captured on film.

Fast motion was classically used to show the supernatural, as in Nosferatu (Murnau, 1922), or to show inhuman action, like a brutal murder. Lately, action films have combined the slow motion effect with fast motion to create a ramping effect. Films like 300 (Snyder, 2007) and Sherlock Holmes (Ritchie, 2009) use ramping to put focus on a character’s isolated movements and their mode of thinking through this movement. By suggesting that only this character would be able to think and act so quickly, ramping suggest supernatural abilities along with a “cool” factor.

Though special effects like ramping are not meant to look realistic, in that we cannot see ramping in the real world with our own eyes, these effects feel realistic because they exist within an immersive story world that has become believable to the audience. Objectivity in cinema does not always align with realism. It is entirely possible for an impossible fantasy space to be realistic. And it is entirely possible for a realistic scenario to be filmed in a way that could not be seen with our own eyes. The camera eye is a subjective point of view even when it is not positioned in a point of view shot. Through cinematography decisions, like camera placement, movement, lenses, color, and special effects, we are displaced from our theater seats and moved into the story world, gazing through a particular vision of this world. This kind of suspension of disbelief allows us to engage with a historical biopic like Ali (Mann, 2001) through just as much imaginative movie “magic” as a technically unrealistic fantasy film like Avatar (Cameron, 2009).

Matte painting: A painting that is composited with live footage to take the place of an on-location set.

Rear projection: Footage is projected onto a backdrop while the actor is filmed in front of it.

Slow motion: Image is captured at a faster speed and so appears to slow down when projected.

Fast motion: Image is captured at a slower speed and so appears to speed up when projected.

Ramping: Fast motion and slow motion used sequentially in a single shot.

Questions for Consideration: Cinematography

- How can color show a character’s journey, or allow for deeper insights into a film’s meaning? Select a single shot or still frame from a film, one that you think is particularly interesting or significant in terms of its use of color. Analyze this still as you would a painting or a photograph. What is the role of color in this still, and how does it challenge the different ways in which the image can be understood?

- Cinematic aspects such as camera angles, camera position, and camera movements are vital to the shifting impact of a film on the viewer. Examine a short film and jot notes under these three categories of cinematography, or any other cinematic choices that capture your imagination. What strikes you as special or impressive, and how do these images make you feel? What do you think is the role of cinematography in the film’s effect on you?

Attribution

FILM APPRECIATION

Dr. Yelizaveta Moss and Dr. Candice Wilson

Acknowledgement

Film Appreciation is dedicated to the remarkable faculty and students of the CMJ department at UNG. Thank you for inspiring us to take on this project.

It is a pleasure to acknowledge and thank those film professors and students who have reviewed the project and contributed to its content. Thank you to the faculty insert contributors Michael Lucker, Dr. Tobias Wilson-Bates, Alex Lukens, and Dr. Jeff Marker. Thank you to the students who contributed their essays as writing samples, Hope Gandy and Eric Azotea. And thank you to the students who piloted the textbook and provided feedback: Peyton Lee, Carly Martinez, Marissa Oda, Danna Sandoval, David Sutherland, and Elise Wilkins.

Copyright

This textbook is an open educational resource developed with funding from an Affordable Learning Georgia Textbook Transformation Grant.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.